My Suborbital Life Blog 3: The Suborbital Revolution Is Here –S. Alan Stern

As I write this blog, I’m about to leave on a business trip to Boston, to lead a science team meeting of the NASA New Horizons mission, which I serve as Principal Investigator (PI) for. The meeting is a typical business trip, one of over a 1000 that I’ve made in my career. My next business trip is as usual replete with admin assistance, travel reimbursement rules, and a post-trip expense report to file. But despite all that, it isn’t a routine trip at all.

I’ll be headed to southern New Mexico for that one, to launch into space on a suborbital research and training mission aboard Virgin Galactic. Without a doubt, it’s going to be the most memorable business trip I’ve ever taken, even topping my unforgettable 1995 astronaut interviews in Houston, and the 2006 launch and 2015 Pluto flyby trips for New Horizons.

Most people who travel to space today are suborbital space tourists. Not here. Instead, I’ll be traveling on behalf of my employer, the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI), as a working researcher, performing specific tasks with specific objectives on the spaceflight.

To me, having spent my entire career to date in the service of space exploration, space development, and the space sciences, going to space to actually work there is a badge of honor, and a very rare one. But I don’t expect that will be the case very much longer.

Why? Because the commercial space revolution is lowering costs and widening access to space in many ways. One of the most important in my view, is the way commercial space is revolutionizing the nature of suborbital research.

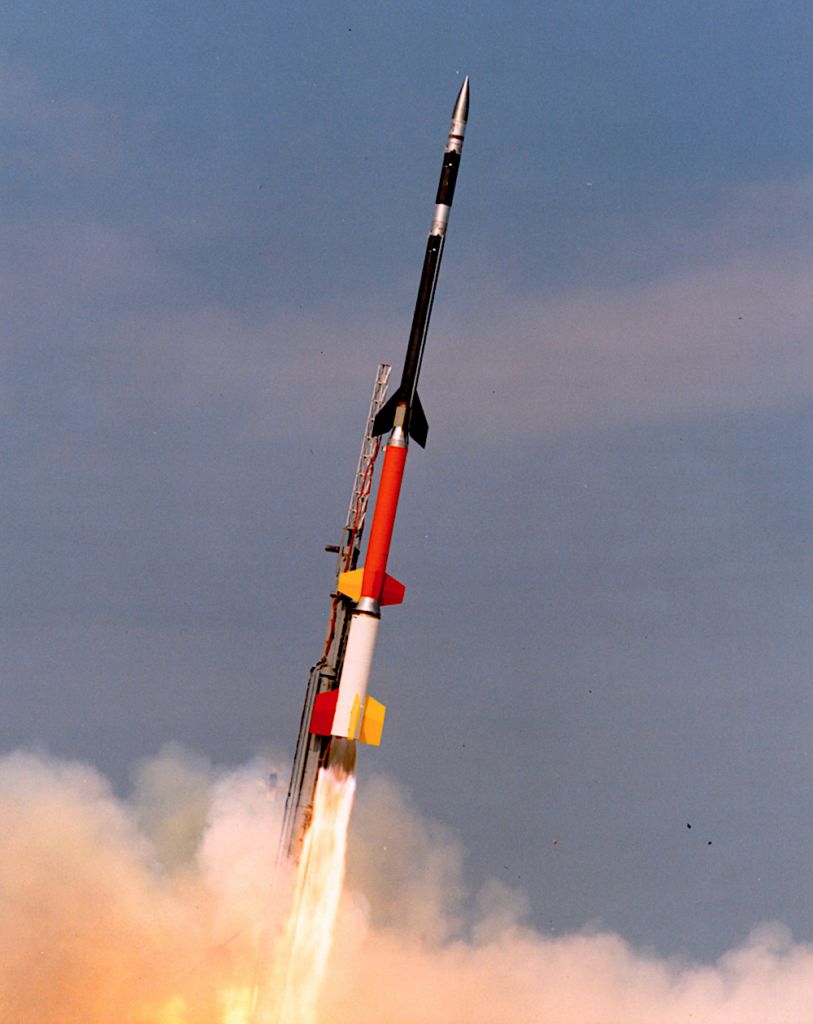

What is suborbital research? It’s the use of rocket- and balloon-powered vehicles to study the Earth and space from altitudes far above those achieved with aircraft. Suborbital research got its first real foothold in high altitude ballooning and post-World War II “unmanned” rocketry in the 1950s. These systems proliferated in the 1960s through the 1980s, when I first became involved. My role initially was as an engineer on University of Colorado “sounding rockets” to study the upper atmosphere and making astronomical observations using ultraviolet spectrometers. Later, as I became a scientist, was on the science team of several other suborbital sounding rockets, and then after earning my PhD, I led seven such suborbital missions as PI. Except for one rocket launched from Poker Flat, Alaska, all of the rocket missions I’ve been involved in flew from White Sands Missile Range (WSMR) in southern New Mexico.

A traditional uncrewed suborbital rocket experiment launches from WSMR (Photo credit: NASA).

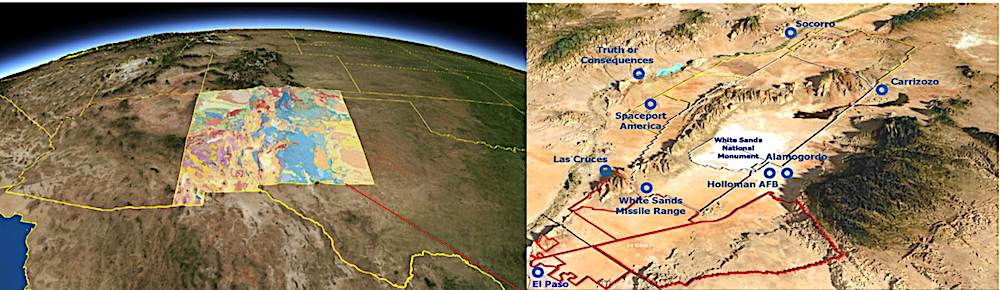

When I was involved in that kind of work, which stretched into the early 2000s, I don’t think I ever imagined that one day I’d launch to space suborbitally from southern New Mexico, and barely around the corner from White Sands on maps of the United States.

But on November 2nd, or soon thereafter, I’ll be doing exactly that. Ascending to an altitude of about 55 miles for a brief but intense space mission—just like the 14 suborbital sounding rocket missions I was involved in as an engineer, a science team member, and later as PI.

New Mexico and its two spaceports, White Sands Missile Range and Spaceport America.

What is game-changing with new generation suborbital rocket systems like those that Virgin Galactic and Blue Origin fly, and with the soon to be flying high-altitude ballooning systems World View and Space Perspective are designing, is twofold.

First, these new vehicles will allow research flights 10x to 100x as often, and at 5x to 10x, and in some cases even 100x lower in cost than the older, legacy rockets and balloons. And in just the same way that the PC revolution that took computing from rare to routine, and from outrageously expensive to a common commodity, the new generation suborbital systems are opening up whole new ways of doing suborbital space research that could have never before happened.

As a result, fields as diverse as space physiology, microgravity research, astrophysics, Earth observation, and education/public outreach are all going to see a proliferation of new applications, expanded access, and the normalization of suborbital research to something more akin to the use of airborne research platforms.

Equally powerfully, if not even more so, is the second great advance these new vehicles offer by carrying experimenters and educators to space. Putting these people in space to do their work means eliminating the costs, risks, and numerous failure modes of automated experiments that the legacy rocket and balloon systems of the 20th Century demanded.

Flying experimenters and educators is also going to dramatically amplify real time experiment innovation in the same way that scientists and educators doing their work on site in volcanology, oceanography, at astronomical observatories, and in laboratories everywhere have always been able to, but which space experimenters and educators simply could not do—until now.

I’m excited to be at the vanguard of this space research revolution, and look forward to flying and doing research in space many times after my upcoming first flight. It might be over the top, but it’s not impossible that our SwRI team toast about who among us will fly to space the most (“First to fifty!”) might just come true before too very long.

Alan Stern is a planetary scientist and aerospace executive. He is a former NASA Associate Administrator for Science, and a former board chair of the Commercial Spaceflight Federation. He has now been a part of 30 NASA, ESA, and commercial spaceflight flight mission teams, 15 of those as mission or instrument Principal Investigator, including the almost $1B New Horizons mission to Pluto and the Kuiper Belt.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.